Caregiving, Health Literacy, Needs Navigation, Trust

There are no “right answers” here, no guarantees, no actual time frames...this is the world that people living with cancer inhabit.

By Christine Wilson

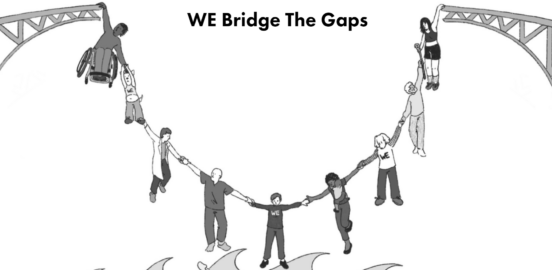

Project Innovation seeks to involve patients, caregivers, advocates and health care providers, researchers and innovators to transform cancer care and treatment.

Part II: Navigation and Support (click here for Part I)

Recently, I paid a visit to a friend, a woman I have known for many years. Until about a year ago, she was an active, healthy person, still playing competitive tennis while maintaining a major role in caring for and keeping her often challenging family together.

Then she was diagnosed with advanced ovarian cancer. At first, her doctors told her she might have six months or less to live, but then things changed for the better. She responded well to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, underwent radical abdominal surgery and then another six months of adjuvant therapy. Her scans look pretty good right now and what initially seemed like a very short run is turning into a longer journey. But she knows– and her doctors confirm– she is by no means cured. The cancer will come back.

The treatment has really taken its toll. She’s tired all the time, has trouble sleeping and little appetite. Her arms and legs tingle. During my visit, she suggested we take a walk in the park near her home. She lasted about 10 minutes before she needed to sit down, catch her breath. Tennis is a distant memory.

Her doctors want her to start a new drug, a maintenance therapy that they say might add six months to her life. Of course, it could be more — or less. The drug has some serious side effects. My friend is tired of feeling sick, tired of being tired. She wants to take a break from the therapy. She talked about three months off treatment and then reconsidering whether she wants to go on the new drug.

So, what do we mean when we talk about shared decision making under circumstances like these? My friend shows me the results of her last scan uploaded on her phone. She gestures at the pile of printouts on her coffee table that lay out the indications for the new drug, its potential benefits and a long list of side effects. She has a lot of information about what is known and not known about this drug. Her doctors don’t recommend a three month break from treatment, but they understand my friend’s desire to escape from the treatment related problems to, in her words, “just feel good again for a little while.”

There are no “right answers” here, no guarantees, no actual time frames, no way to know whether she will get every possible side effect of the new drug or none of them; whether she will be the outlier who responds for years, or not at all. This is the world that people living with cancer inhabit. Unless there is a new therapeutic development, which these days is a slim but not totally unreasonable hope, they will never be cured of their cancers. They will always be involved in juggling a series of imperfect options, knowing that whatever choice they make will have a cost and that in all likelihood, while they can move the pieces around, the cancer will call checkmate in the end.

When what we might term “long” cancer patients talk about support and navigation, they almost always mean people, not printouts. The clinical information is important, necessary, but what they ask for is someone not something to help them think through their choices, feel as comfortable as possible with making these hard choices and accepting their outcomes. Patients want their doctors, or nurses, or navigators to talk through the issues, not just the response rates or disease-free intervals but things that matter to them as people: as mothers, wives, daughters or even tennis players. They deeply appreciate the “peer” support that only those who share their experience bring to the discussion.

For the growing number of people who are living for years with their cancers, the concept of quality of life has real meaning. For providers taking care of these patients, care planning means more than deciding the next course of therapy, more than handing that person a pile of papers. It requires ongoing, conscious, and yes, personal support at every decision point on what can often be a long, arduous and frightening journey. When we talk about developing and implementing decision support tools, integrating them into clinical practice, we can never forget that the most important resource is the relationship between the person who has the cancer and the people who treat, and care for, that patient.

Our discussion group expressed their thoughts on the meaning of support and navigation. For more information, visit Project Innovation.

“I wanted to make sure that people’s experiences were better than mine…I wanted to bring everyone together so that all of our expertise, all of our lived experience, the experience of patients, of healthcare providers, of our families and communities is heard and valued as equal parts of the conversation.” Gwen Darien, NPAF

“I think the most comforting thing I have heard at these decision points is that there is no wrong answer. They have given me some good options and I have tended to favor decisions that are in alignment with my priority of quality of life.” Larry, lung cancer

“I said I’m going to get a second opinion…and I walked in, after he greeted me, I had a long list of questions that no one would answer, and he had read all my records, and he answered every one of those questions. The good doctor is going to listen to you, to encourage you to speak up.” Sally, lung cancer

“I guess I’m talking about needing a nurse navigator or someone whose knowledgeable to step in and take care of you at the beginning, to advocate for you, because doctors are busy and they jump over things. And sometimes, you’re scared and you want that person who can step in and explain things, and help you.” Tia, breast cancer

“I think a lot of organizations over educate. They give you this big binder, and you see that, and it’s just too much information. And you think, is that all going to happen to me? Support is having bite-size information that people can process and grow and learn as they are going through the journey. Because, especially for people with metastatic cancer, we all know, it’s a long journey, not a short trip.” Amelia, breast cancer

Caregiving, Health Literacy, Needs Navigation, Trust

Equity, Health Literacy, Insurance, Policy Consortium

Costs, Health Literacy, Insurance, Needs Navigation, Trust

Health Literacy